Grid, Infrastructure and System Reliability

Energy Transmission and Distribution Infrastructure

Energy transport and distribution infrastructure is included in MESSAGE at a level relevant to represent the associated costs as well as transmission and distribution losses. Within individual model regions the capital stock of transmission and distribution infrastructure and its turnover is modeled for the following set of energy carriers:

electricity

district heat

natural gas

hydrogen

For all solid (coal, biomass) and liquid energy carriers (oil products, biofuels, fossil synfuels) a simpler approach is taken and only transmission and distribution losses and costs are taken into account.

Inter-regional energy transmission infrastructure, such as natural gas pipelines and high voltage electricity grids, are also represented between geographically adjacent regions. Solid and liquid fuel trade is, similar to the transmission and distribution within regions, modeled by taking into account distribution losses and costs. A special case are gases that can be traded in liquified form, i.e. liquified natural gas (LNG) and liquid hydrogen, where liquefaction and re-gasification infrastructure is explicitly represented in addition to the actual transport process.

Systems Integration and Reliability

The global MESSAGE model includes a single annual time period within each modeling year characterized by average annual load and 11 geographic regions. Seasonal and diurnal load curves and spatial issues such as transmission constraints or renewable resource heterogeneity are treated in a stylized way in the model. The mechanism to represent power system reliability in MESSAGE is based on (Sullivan et al., 2013 [107]). This method elevates the stylization of temporal resolution by introducing two concepts, peak reserve capacity and general-timescale flexibility (for mathematical representation see this Section). To represent capacity reserves in MESSAGE, a requirement is defined that each region build sufficient firm generating capacity to maintain reliability through reasonable load and contingency events. As a proxy for complex system reliability metrics, a reserve margin-based metric was used, setting the capacity requirement at a multiple of average load, based on electric-system parameters. While many of the same issues apply to both electricity from wind and solar energy, the description below focuses on wind.

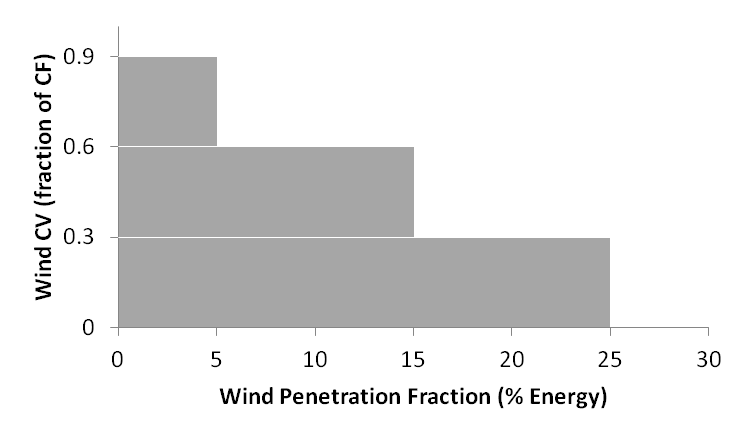

Toward meeting the firm capacity requirement, conventional generating technologies contribute their nameplate generation capacity while variable renewables contribute a capacity value that declines as the market share of the technology increases. This reflects the fact that wind and solar generators do not always generate when needed, and that their output is generally self-correlated. In order to adjust wind capacity values for different levels of penetration, it was necessary to introduce a stepwise-linear supply curve for wind power (shown in the Fig. 12 below). Each bin covers a range of wind penetration levels as fraction of load and has discrete coefficients for the two constraints. The bins are predefined, and therefore are not able to allow, for example, resource diversification to increase capacity value at a given level of wind penetration.

Fig. 12 Parameterization of Wind Capacity Value.

The capacity value bins are independent of the wind supply curve bins that already existed in MESSAGE, which are based on quality of the wind resource. That supply curve is defined by absolute wind capacity built, not fraction of load; and the bins differ based on their annual average capacity factor, not capacity value. Solar PV is treated in a similar way as wind with the parameters obviously being different ones. In contrast, concentrating solar power (CSP) is modeled very much like dispatchable power plants in MESSAGE, because it is assumed to come with several hours of thermal storage, making it almost capable of running in baseload mode.

In order to ensure adequate reserve dispatch, dynamic shadow prices are placed on capacity investments of intermittent technologies (e.g., wind and solar). The prices are a function of the cumulative installed capacity of the intermittent technologies, the ability for the convential power supply to act as reserve dispatch, and the demand-side reliability requirements. For instance, a large amount of storage capacity should, all else being equal, lower the shadow price for additional wind. Conversely, an inflexible, coal- or nuclear-heavy generating base should increase the cost of investment in wind by demanding additional expenditures in the form of natural gas combustion turbines or storage or improved demand-side management to maintain system reliability.

Starting from the energy metric used in MESSAGE (electricity is considered as annual average load; there are no time-slices or load-curves), the flexibility requirement uses MWh of generation as its unit of note. The metric is inherently limited because operating reserves are often characterized by energy not-generated: a natural gas combustion turbine (gas CT) that is standing by, ready to start-up at a moment’s notice; a combined-cycle plant operating below its peak output to enable ramping in the event of a surge in demand. Nevertheless, because there is generally a portion of generation associated with providing operating reserves (e.g. that on-call gas CT plant will be called some fraction of the time), it is posited that using generated energy to gauge flexibility is a reasonable metric considering the simplifications that need to be made. Furthermore, ancillary services associated with ramping and peaking often do involve real energy generation, and variable renewable technologies generally increase the need for ramping.

Electric-sector flexibility in MESSAGE is represented as follows: each generating technology is assigned a coefficient between -1 and 1 representing (if positive) the fraction of generation from that technology that is considered to be flexible or (if negative) the additional flexible generation required for each unit of generation from that technology. Load also has a parameter (a negative one) representing the amount of flexible energy the system requires solely to meet changes and uncertainty in load. Table 17 below displays the parameters that were estimated using a unit-commitment model that commits and dispatches a fixed generation system at hourly resolution to meet load an ancilliary service requirements while hewing to generator and transmission operation limitations (Sullivan et al., 2013 [107]). Technologies that were not included in the unit-commitment model (nuclear, hydrogen electrolysis, solar PV) have estimated coefficients.

Technology |

Flexibility Parameter |

|---|---|

Load |

-0.1 |

Wind |

-0.08 |

Solar PV |

-0.05 |

Geothermal |

0 |

Nuclear |

0 |

Coal |

0.15 |

Biopower |

0.3 |

Gas CC |

0.5 |

Hydropower |

0.5 |

H2 Electrolysis |

0.5 |

Oil/Gas Steam |

1 |

Gas CT |

1 |

Electricity Storage |

1 |

Thus, a technology like a natural gas combustion turbine, used almost exclusively for ancillary services, has a flexibility coefficient of 1, while a coal plant, which provides mostly bulk power but can supply some ancillary services, has a small, positive coefficient. Electric storage systems (e.g., pumped hydropower, compressed air storage, flow batteries) and flexible demand-side technologies like hydrogen-production contribute as well. Meanwhile, wind power and solar PV, which require additional system flexibility to smooth out fluctuations, have negative flexibility coefficients.